Originally published in the In Jerusalem, December 9, 2016

When I was 17, my mother sent me to Auschwitz. Now that my son is 17, my husband and I sent him too.

I was a teenager living in the US. He is a teenager living in Israel. I went with the March of the Living because my mother (God bless her) insisted upon it. He went through school with nearly all of his classmates as many Israelis do in the 12th grade.

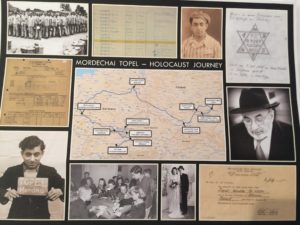

I went knowing that my grandparents had watched their children murdered before their eyes. I had sat with them as they cried, lost in memories I never heard from their own lips.My son was shipped off with a binder full of his family history. His paternal great-grandfather never stopped bearing witness in video, written, and photographic testimony.

My grandparents hid. In barns, woods, wherever they could, trying to keep their remaining relatives alive. My grandmother became a partisan when all her siblings, children, nieces and nephews had been lost to her.

My husband’s grandparents survived multiple camps and death marches and became nearly the sole survivors of their previously large families.

As I walked through the silent forest, with Polish police surrounding us, I imaged my grandparents hiding from the Nazis under fallen trees and in ditches. My son stood in a gas chamber similar to the one his zaide (Yiddish for grandfather) stood in as he waited to die like his parents and siblings before him, but was saved when water rained down instead of gas.

The school asked all of the parents to write letters which would be given to the boys after they visited Yaar Hayeladim, a forest site where hundreds of Jewish children, as well as hundred of others, lay in several mass graves. We did not know what he would be thinking, or what he would want to hear, so we said the things we most wanted him to gain from his experience.

This is the letter we wrote:

“As parents, all we want to do is protect our children. We sooth your scrapes and work hard to put you in places where you will grow and learn and be safe and protected. We fight bullies and we kiss away your tears. But, at some point, we must stop shielding you and let you learn about the evils of the world and all that man is capable of. It is a lesson you must learn so that you can do your part to make sure that it never happens again, not on a large scale and not on a small scale.

“Every minute of every day you choose who you want to be and how you will react to any given situation. What you are experiencing now in Poland is the worst that man can do. It is what your family suffered and it is what makes us who we are today as a family and as a nation. It is your legacy as a person and as a Jew.

“There is no way to hide from it. It happened. And today, at this moment around the world, similar things are happening. Though it is painful – very, very painful – you must see it, hear it, touch it, and feel it. It will hurt and it may take you to your knees. Let it. Don’t hide from it. This is the only way it will become a part of who you are. A part of the man you are becoming. It will sit inside of you forever. It won’t always hurt, for it will morph into a source of strength and conviction. It will be the place you draw from when you must stand up for something or someone.

“You are proof that evil does not win. That you are back in Poland, the third generation after the Shoah, standing where your family members were gathered, humiliated, and gassed for being Jews, means that the worst plot in history failed. That you are Israeli, a Jew living in the State of Israel, proud, strong, and with a healthy understanding of right and wrong, rebuilding the nation that was brought lower than any other in history, is the greatest testament to our spirit for life and freedom.

“You are a link in the chain unbroken since Avraham. We could not possibly be prouder of you. Feel the pain but don’t let it break you. Understand the import of what you are witnessing, but don’t feel hate beyond that for evil. Learn, understand, bear witness and come out stronger. This is your legacy.”

On his last day, he read his Alta-Zeidi’s (Great grandfather’s) story to the group at the entrance to Birkenau, one of the places where he had been a prisoner. My son spoke of how meaningful it was to have known his great-grandfather, to have known his story in his own words. To stand where he stood, walk where he walked, touch what he touched. It all turned something difficult to relate to, into something intensely personal.

On his return, we met him and his group at 5:30 in the morning in Jerusalem’s Old City. They were exhausted, but danced and waved flags.

Recalling my own need for time to process, we didn’t bombard him with questions, but simply asked him for his overall feelings. He said that he didn’t like being in Poland, but he believes that every Jew should go. And as much as he has always been my Sabra and a proud Zionist, he said that Poland solidified just how vital it is that the Jews have a home and are able to defend themselves.

Ironically, or perhaps the opposite of ironically, it was my trip to Poland that lead to my son to being Israeli. Though a generation apart, our conclusions were much the same.

It is not only Jewish children who should walk the barracks of Auschwitz, touch the scratches in the walls of the gas chambers, and weep at the ash mound of Majdanek, all that is left of the humans burned there. For, those who inherit the past must also inherit its lessons. And the world will not recognize the subtle signs of tyranny, the slow path to genocide, if they do not know how it began and where it led. Our children will not know the value, importance, and the absolute critical need for the Jewish state if they do not understand how close the world came to making the Jewish people a memory.

Those of us who understand what happens when people dehumanize others must speak out in every generation, wherever we see it, and we must teach our children to do the same. We cannot afford to forget what it cost us so dearly to learn. We need to touch it and internalize it – in every generation.